Part of the task of any home server room, vintage or otherwise, is monitoring. After all, you're now your own L1, L2 and L3 support. A camera passively observes the room that can be remotely viewed. The main server can generate alerts if it fails over to a UPS (power outage, blown supply, etc.). If the WAN connection goes down, an SMS gateway can communicate with me by text message and I can query it about the state of the internal network. I use an SMSEagle for that, basically a Raspberry Pi in a cool case with an LTE modem running modified Raspbian (which I naturally have modified further). All of the systems can send it alerts for broadcast via its internal APIs.

(The USB device plugged into it I'll discuss a little later.)That leaves environmental controls. Here in Southern California, winters aren't that cold, so the major need is cooling during summer and fall. The room is cooled by a 12,000 BTU portable air conditioner that vents to an outflow portal on the roof and whose power is controlled by a programmable power strip. The A/C turns itself off and on based on its thermostat but the A/C isn't network enabled, so I need to know what temperature it actually is in the room, and whether the air conditioner is in fact running — ideally something that would assess if there's airflow.

The temperature sensor is a THUM.

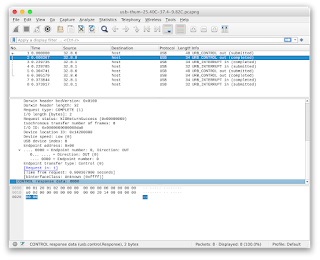

I bought it back in the day because they had a native Power Mac command line client, but now that I have other things I'd like to connect it to (and the client was closed-source, at least at the time), I decided to reverse-engineer the protocol. Naturally, the first thing to do when you're doing that is to crack it open. Internally the THUM is actually a relatively simple device. A small Sensirion SHT75 temperature and humidity sensor sticks out of the side of the case and is connected to a PIC 16C745-I/SP, which is the main chip dominating the board (the TMS SN65240 is there to suppress transient signals on the USB port). The theory of operation is thus fairly obvious: the PIC merely reads raw sensor data from the SHT75 and provides it to the connected system (it shows up as a USB HID). The next step was thus to reverse-engineer the actual wire protocol.Snooping on a mysterious USB device is most easily done with the USB monitoring tools in Wireshark. I installed it on my MacBook Air and, with Wireshark running, would run the closed-source THUM Mac tool, note the temperature and relative humidity the official client reported, and then save the trace. Here's an example.

Every single session showed two URB_CONTROL and URB_INTERRUPT couplets. The control from the connected Mac was a two byte message, first 00 00 (which appears to be a temperature command), and then 01 00 (which appeared to be humidity). The THUM would then reply with its own two byte response. One would assume any reported value would increase as temperature and humidity both increased, so looking at the reports this value was most likely a 16-bit big-endian (yay!) unsigned short. I made a number of readings and then plugged them into LibreOffice. Using LibreOffice's regression analysis tools, the fit is perfectly linear (assuming, of course, the sensor doesn't vary at its extents, which is always a risk with sensors) and we should now have an accurate intercept and slope to compute temperature in Centigrade from the provided value.Humidity was a little harder, as relative humidity depends on temperature to determine how much water vapour the surrounding air can actually carry, and I wasn't able to get a good regression fit. After messing around with the numbers some, it dawned on me I could just go pull the datasheet for the sensor to see if the manufacturer had any coefficients I could plug in. Not only did the datasheet have a nice graph, it actually had formulae for computing a linear relative humidity value from the sensor value, and then to adjust it for the observed temperature. The formula matched the official THUM client's computation perfectly.

Now we have all the steps needed to actually write our own client, so I did, which I'll link to at the end (the same C source file compiles on Mac OS X and Linux). The only other glitch I ran into was that you must fetch the humidity after you fetch the temperature, and you must read both; you can't just fetch one or the other. If you try to do that, the PIC may flip out and even stop responding to you until the box is reset.

As a post-script, the datasheet also contained a formula for the temperature (as well as the valid ranges), but the coefficients didn't quite match my linear regression values. Later on someone at Practical Design Group responded to my E-mail and put up source code and pre-built binaries for the Raspberry Pi. This client seemed slower than my own client on my Raptor Talos II (and there wasn't Mac source code), so I'm sticking with my homebrew version, which is what runs on the G4 server now (which runs OS X Tiger). Interestingly Practical uses the Sensirion formulae for relative humidity, but their coefficients matched mine for computing temperature, so I kept those also.

Now, airflow. I decided an easy approach would be to monitor sound levels, since any audio pickup with its wind screen off will detect air passing by as noise. As an added bonus, if any alarms were going off, dying cooling fans, dying other things (always a possibility with old hardware), etc., the resulting audio disturbance would also be detectable.

The most inexpensive and easy way to get "live" USB-based decibel meters are versions of the GM1356, shown here in operation "monitoring" the air conditioning unit.

This ubiquitous meter is easily recognized by its six-button control panel and standard case and accessories, and was rebadged by a number of manufacturers (here a BAFX 3608) with logging software for Microsoft Windows. Fortunately some enterprising soul had already written a Ruby-based monitor for this device, so I figured it would be a simple matter to convert it to C and have it run on the G4 server too. I patterned off the same code I used to query the HID for the THUM, plugged it into the G5, and ... nothing but errors trying to talk to it. On the possibility this device was uncovering an irregularity with HID support in OS X Tiger, I plugged it into my NetBSD G4 Mac mini. It said there was a problem with the device and disabled the port.Now wondering if I had a defective unit, I then plugged it into my Linux Raptor Talos II, determined its vendor and ID with lsusb and tried to pull a device report with lsusb -v -d 64bd:74e3. Besides showing an impossible HID polling interval of zero (!), lsusb did faithfully display the USB configuration report but then hung up and timed out with cannot read device status, Resource temporarily unavailable (11). At this point, since they were cheap, I bought a second one. It did the exact same thing.

It turns out this unit is obnoxiously non-compliant with the USB HID standard, just enough to work with Windows, which is its only supported platform. You can't use normal HID queries with it on apparently any operating system (for that matter, Linux libhid doesn't like it either), but if you send raw queries with usb_interrupt_write and usb_interrupt_read you can get something out of it in Linux, at least. I gave up trying to get OS X IOKit to play nice, so after porting the Ruby client to C on the Talos II, I put it on the only Linux system I have running in the vintage server room — the Raspbian SMSEagle. And that's what you see connected to it.

Does this work for monitoring? After all that, yes. I took some measurements and the baseline noise in the server room ranges from 54 to 56dB depending on how warm it is (on warmer days the cooling fans are louder). When the A/C comes on, it runs at full blast and the device picks up the airflow at 60dB+. This is a significant and easily noticed jump, so this benighted piece-of-crap still ends up being more than enough to know if the A/C's actually hauling A.

The next thing I'll add, probably in whatever crumbling shack we're able to afford in this hideous housing market, is power monitoring. While I can control outlets, I can't really determine short of manually grabbing a Kill-O-Watt how much draw is occurring on any given circuit or power strip. It would be nice to know who's sucking the amps other than, of course, the beasts themselves. They get a pass because they're still doing useful work, even if they aren't as sexy or efficient anymore.

The C code for the THUM command line tool (OS X, at least 10.4, possibly earlier and Linux) and GM1356 command line tool (Linux) are available as Github gists.

0 Comments